Cycle helmet laws – facts, figures and consequences

Paper presented by DL Robinson at The International Bicycle Conference, Velo Australis, Freemantle, 1996

Introduction

Few delegates at this conference need to be convinced of the benefits of cycling, either as an environmentally friendly, pollution free transport, or as healthy exercise. Indeed, the British Medical Association reported: (despite the risk of accidents) "car travel is more deleterious to health unless the motorist can exercise several times a week by other means that will maintain fitness" (BMA, 1992). Nowadays, only a minority of the population takes sufficient exercise and several billions are spent every year on hospital treatment of heart and circulatory disease, much of which might be prevented by regular exercise such as cycling. Cycle helmets may be beneficial if they help reduce the risk of head injury, but many cyclists find them hot or uncomfortable. Helmet laws might therefore be counter-productive if they discourage cycling sufficiently for the loss of health and social benefits from reduced cycling to outweigh gains from fewer head injuries. Here, an attempt is made to shed light on this difficult question by reviewing available statistics on head injuries and cycling participation before and after helmet laws were passed in Australia.

Helmet laws and cycling activity

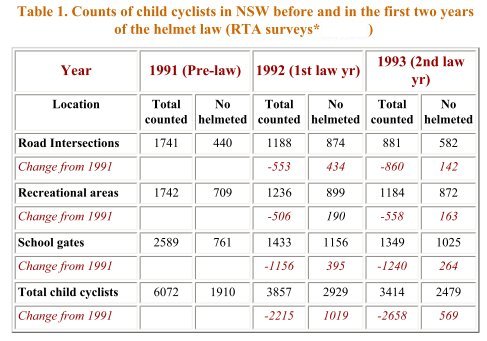

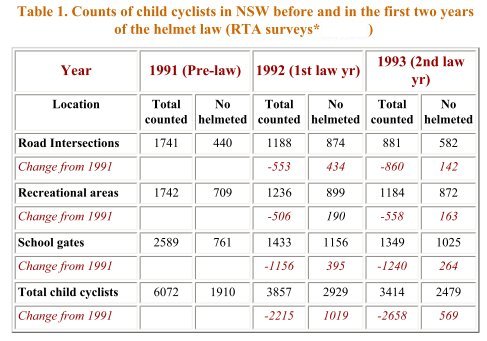

Only two states - Victoria and NSW - attempted to measure the effect of the laws on cycling activity by pre- and post-law surveys at the same sites, observation periods, time of year and, where possible, the same observers. In NSW, data from identical pre- and post-law surveys were available only for children. Both surveys were conducted in excellent weather. Table 1 shows that the increase in numbers wearing helmets was only about half the decrease in cyclists counted, with similar outcomes for cycling in recreational areas, through road intersections, or to school. Reductions in rural NSW (35%) and in the Sydney Metropolitan area (37%) were almost identical. Another survey was carried out a year later, under fine and generally sunny conditions. Even fewer cyclists were counted.

Sources: Cameron, Heiman and Neiger, 1992, Smith and Milthorpe, 1993

Source: Finch, Heiman and Neiger, 1993

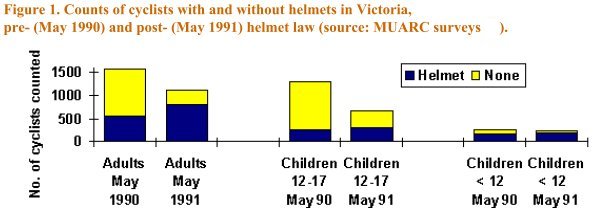

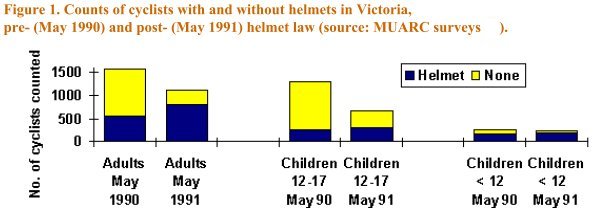

In Victoria, both adults and child cyclists were counted. The same sites and observation times were used and 82% of sites had the same weather classification. Overall, 36% fewer cyclists were counted (Figure 1). For sites which were fine in both 1990 and 1991, the reduction was, however, only 24%. The survey was repeated the following year, when a bicycle rally happened to pass through one of the sites. Excluding this site, numbers in the second year were down by 27% on the pre-law survey. These figures indicate, as in NSW, that the increase in numbers wearing helmets was less than the overall decrease in numbers of cyclists.

Attitude surveys confirm the potential of helmet laws to discourage cycling. A total of 1,210 secondary school students were questioned as part of the Blacktown Bike Plan. Of those who had not ridden in the past week, helmet restriction was the most common reason (33.9%) compared with unsafe (11.8%) or even not owning a bike (33.8%). A street survey in the Northern Territory of more than 800 people found 20% had given up cycling because of the law and a total of 42% had reduced their cycling. In the ACT, when 325 cyclists were asked "Would you cycle less if helmets became compulsory?" 90 (28%) said they would. In Western Australia (WA), a telephone survey of 254 households in which adults responded on behalf of themselves and their children found 13% of Perth and 8% of country cyclists had given up or cycled less because of the law (Heathcote, 1993). However, when the adult respondents replied for themselves, a proportion equivalent to 64% of current adult cyclists said they would cycle more if not legally required to wear a helmet. Thus, apart from the WA telephone survey (suffering from a small sample size and that parents may not always be aware of a child's true motives), street counts and survey interviews have both consistently revealed a substantial deterrent of helmet laws on cycling.

Head injuries

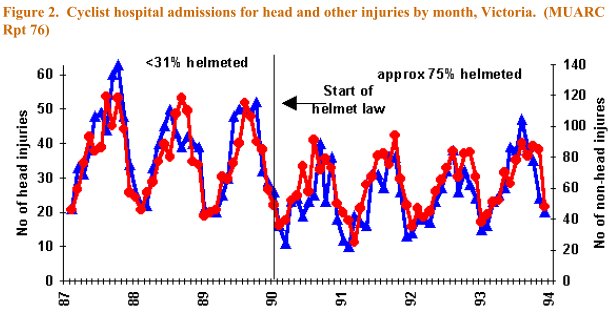

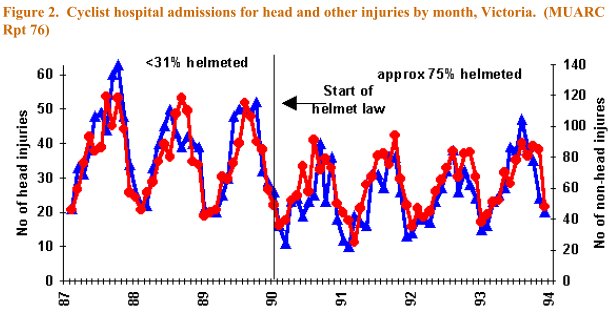

Figure 2 shows hospital admissions of cyclists for head and other injuries in Victoria in the years before and after the helmet law. Non-head injury admissions (right hand axis of graph) outnumbered those for head injury by a factor of approximately 2:1, both before and after the law. Consistent with surveys indicating reduced cycling, the effect of the law can be clearly seen by a reduction in both head and non- head injury admissions, but, despite a substantial increase in helmet wearing from 31% of cyclists to 75%, the relative proportions of the two appear little changed.

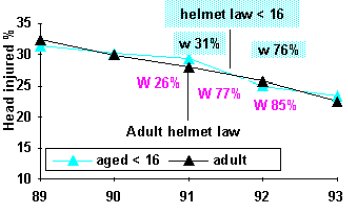

Figure 3. NSW. Helmet wearing (w%) and cyclist hospital admissions by year to end June. NB: Law for children introduced 6 months after adult law

Sources: Cameron, Heiman and Neiger, 1992, Smith and Milthorpe, 1993

|

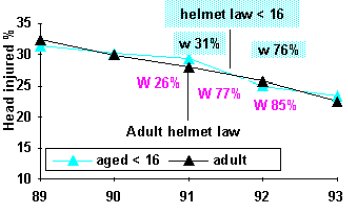

Figure 3 shows pre- and post-law helmet wearing rates in NSW (Cameron, Heiman and Neiger, 1992, Smith and Milthorpe, 1993) together with hospital data. A generally declining trend is apparent in the percentage of adult cyclists admitted to hospital suffering head injuries, but no clear effect of the helmet law, estimated to have increased helmet wearing rates from 26% to 77% and 85% of adults in the 1st and 2nd years of the law. For child cyclists, a small reduction can be seen in the percentages with head injury over and above a generally declining trend. However, head injuries to child cyclists declined by only 29% in years 1 and 2, compared with reductions of 36% and 44% in numbers of child cyclists observed.

|

If the surveys were representative of the effect of the law on cycling participation, then the risk of head injury would appear to have increased, rather than decreased, because of an increase in accident rates. Researchers have developed the theory of risk compensation to explain why accidents often appear to increase following adoption of a new safety measure. In many cases, the benefits of the measures are large and outweigh any effects of risk compensation. Comparison of head injury and cycling participation rates following helmet laws in NSW and other places leads to the possibility this is not the case for bike helmets.

|

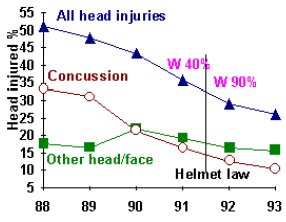

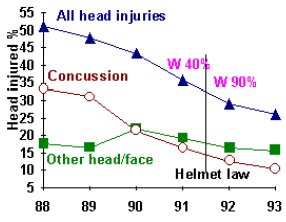

Hospital data for South Australia (SA) (Marshall and White, 1994) is given in Figure 4. Percentage of cyclist admissions are graphed separately for those suffering concussion and other head/face injuries. The steady decline in admissions for concussion may, in part, relate to changes in admissions policy in that some hospitals no longer routinely admit patients who suffered a short episode of concussion (Kraus, Fife and Conroy, 1987). No additional effect of the law is apparent on concussions. For other head injuries, the effect is difficult to determine. Rates were no different in 1992-3 with mandatory helmets than in 1988-89 when wearing was limited. We may therefore conclude increasing helmet wearing from 40 to 90% of all cyclists had a relatively small effect, compared with other factors affecting the risk of head injury. A similar conclusion was obtained from head injury data in New Zealand. As in the Australian data, trends were apparent in rates of head injury and noted to be "present before, and independent of, helmet wearing" (Scuffham and Langley, 1997). After accounting for this trend, increased helmet wearing had "little association with serious head injuries as a percentage of all serious injuries to cyclists" (Scuffham and Langley, 1997).

|

Figure 4 South Australia . Cyclist hospital admissions and helmet wearing (%w) by year to June

source: Marshall and White, 1994

|

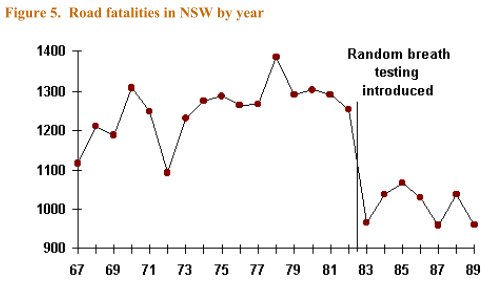

Other road safety measures

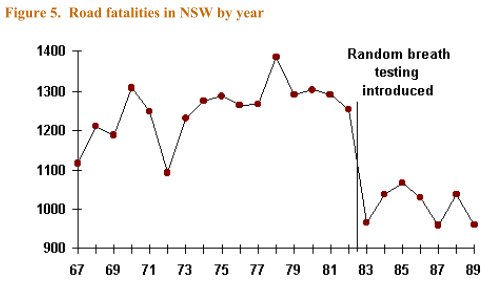

The relatively small effects of the helmet laws (except on numbers of cyclists) contrasts starkly with other measures such as random breath testing (RBT), introduced in NSW in December 1982. Other recent measures have included the highly successful Transport Accident Commission (TAC) road safety campaign in Victoria which reduced accident costs by AUD 220 million for an outlay of AUD 5.5 million (Powles and Gifford, 1993). Included was a crack-down on speeding and drink-driving via speed cameras and increased RBT ('booze busses'). Pedestrian fatalities in Victoria fell from 159 in 1989 to 93 the following year (FORS, 1990).

These initiatives started around the same time as the helmet law. Comparing the two years before the helmet law with the following two, the percentage of TAC pedestrian injury claims involving death or head injury fell by 4.2 from 19.6% to 15.4% Despite increased helmet wearing from 31%-75%, the decrease for cyclists injured in collisions with vehicles was 3.1, from 12.0% to 8.9%. While some of this may have been due to helmets, the large effect seen for pedestrians, together with comparatively small effects for cyclists in accidents not involving motor vehicles, makes it plausible that a substantial proportion of this effect, previously attributed entirely to increased helmet wearing, may, in fact, have been due to the effective TAC campaign.

Conclusions

The fact that little or no obvious effect can be seen in hospital data does not imply cyclists choosing to wear lightweight, comfortable, well fitting helmets, will not benefit, provided they do not ride on more dangerous roads or take less care. The relatively small effects from helmet laws must, however, be contrasted with the large effect on numbers of cyclists and better responses from other road safety campaigns.

References

BMA, 1992

Cycling towards health and safety. British Medical Association ISBN 0-19-286151-4.1992.

Cameron, Heiman and Neiger, 1992

Cameron M, Heiman L, Neiger D, 1992. Evaluation of the Bicycle Helmet Wearing Law in Victoria During its First 12 Months. Monash University Accident Research Centre Report 32.

Finch, Heiman and Neiger, 1993

Finch C, Heiman L, Neiger D, 1993. Bicycle Use and Helmet Wearing Rates in Melbourne, 1987 to 1992: the influence of the helmet wearing law. Monash University Accident Research Centre Report 45.

FORS, 1990

Road traffic fatalities Australia. Federal Office of Road Safety, Canberra, 1989 and 1990.

Heathcote, 1993

Heathcote B, 1993. Bicycle helmet wearing in Western Australia. Western Australia Police Department .

King and Fraine, 1993

King M, Fraine G, 1993. Bicycle helmet legislation and enforcement in Queensland 1991-3: effects on helmet wearing and crashes. Queensland Transport, Brisbane June 1993.

Kraus, Fife and Conroy, 1987

Kraus JF, Fife D, Conroy C, 1987. Incidence, severity and outcomes of brain injuries involving bicycles. American Journal of Public Health 1987;77:76-78..

Marshall and White, 1994

Marshall J, White M, 1994. Evaluation of the compulsory helmet wearing legislation for bicyclists in South Australia. South Australia Dept of Transport Report 8/94.

Ozanne-Smith, 1993

Bicycle related injuries. Hazard (various issues) published by Victorian Injury Surveillance System, 1993.

Powles and Gifford, 1993

Powles JW, Gifford S, 1993. Health of nations: lessons from Victoria, Australia. BMJ 1993 Jan 9;306(6870):125-7.

Scuffham and Langley, 1997

Scuffham PA, Langley JD, 1997. Trends in cycle injury in New Zealand under voluntary helmet use. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1997 Jan;29(1):1-9.

Smith and Milthorpe, 1993

Smith NC, Milthorpe MW, 1993. An Observational Survey of Law Compliance and Helmet Wearing by Bicyclists in New South Wales - 1993 (4th survey). NSW Roads & Traffic Authority ISBN 0-7305-9110-7.