Costs and benefits of the New Zealand helmet law

Robinson DL

No effect of the helmet law over and above a general trend

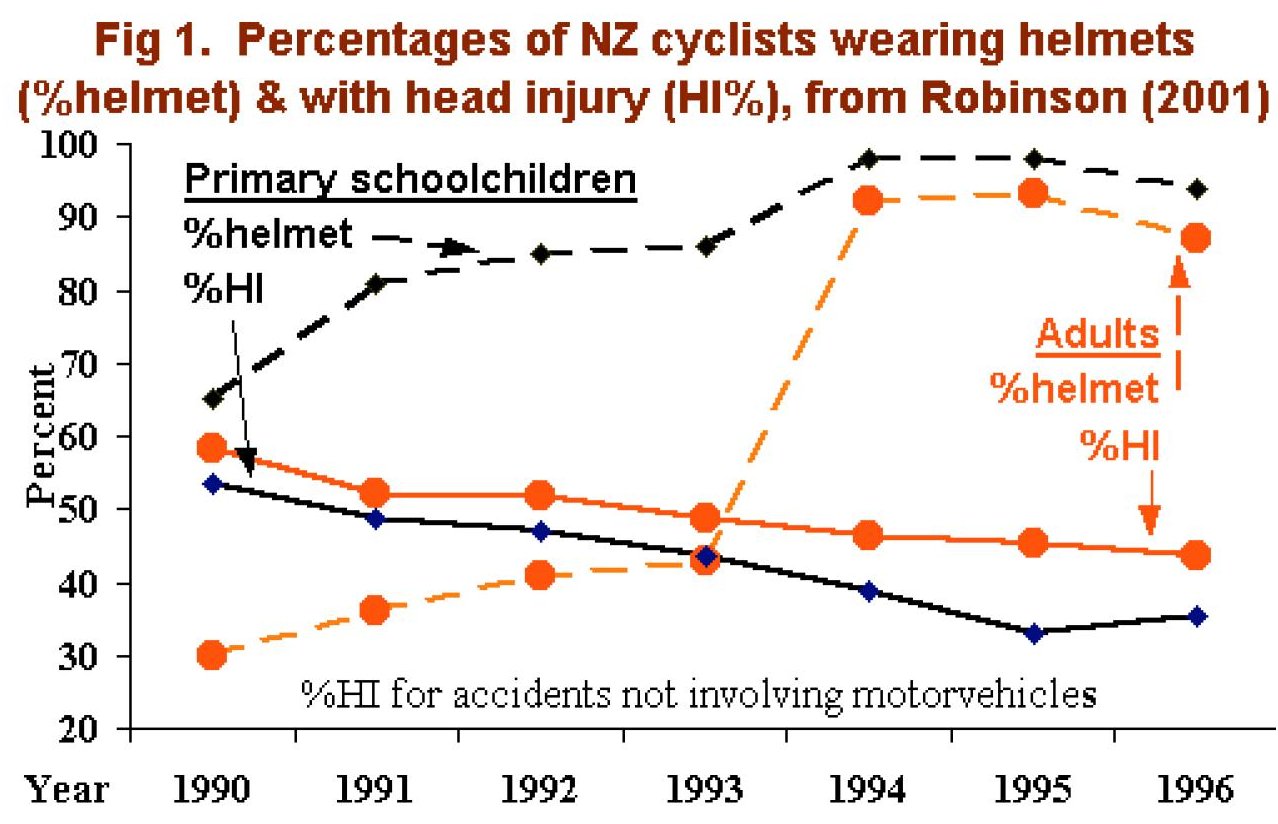

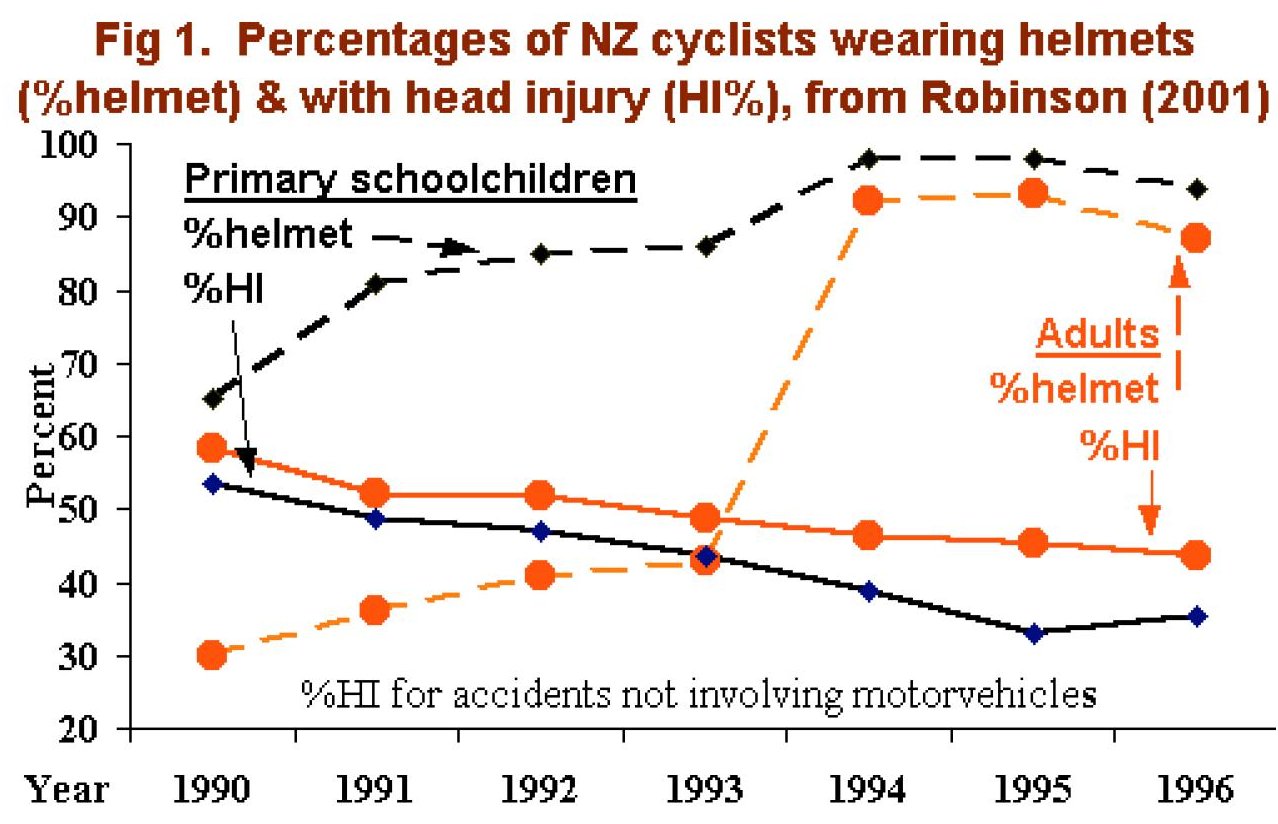

Adult cycle helmet wearing rates increased dramatically (from 43% in 1993 to 92% in 1994) with the New Zealand (NZ) helmet law (Fig1, red dashed line). In contrast, most primary school children were already wearing helmets before the law (86%), so their helmet-wearing rate increased by only a small amount.

If helmets had a major impact on head injury rates, we would expect a substantial fall in the percentage of adult cyclists with head injury, due to the 43% to 92% increase in wearing, but a more modest change for primary school children.

Figure 1 shows this didn't happen. There was a downward trend in head injury rates for both primary school children and adults, but no sudden change when adult helmet wearing rose from 43% to 92%.

|

Many researchers (e.g. Robinson, 1996, Hendrie, Legge, Rosman and Kirov, 1999) have observed trends in head injury rates of cyclists, pedestrians, motor vehicle occupants and other road users. The slow, gradual fall in head injury rates of adult cyclists in NZ (Fig. 1) cannot be anything other than a trend. The change in HI% from 1993 to 1994 was no different to any other year, despite the 43% - 92% increase in helmet wearing. How could this possibly be an effect of increased helmet wearing? The data (details of which are provided in Appendix 2) strongly suggest there was no real detectable benefit of the NZ helmet law.

|

Several researchers have examined head injury data following NZ's helmet law. Figure 1 is based on head injuries and limb fractures for cyclists admitted to hospitals in NZ (Robinson, 2001). Scuffham, Alsop, Cryer and Langley, 2000 analysed a slightly different dataset consisting of all cyclist admissions to public hospitals in NZ. Scuffham noted the presence of trends and that: "the addition of a time trend component caused the helmet wearing proportion to become insignificant." Thus, if trends were fitted, no researcher could detect any significant effect of NZ's helmet law.

|

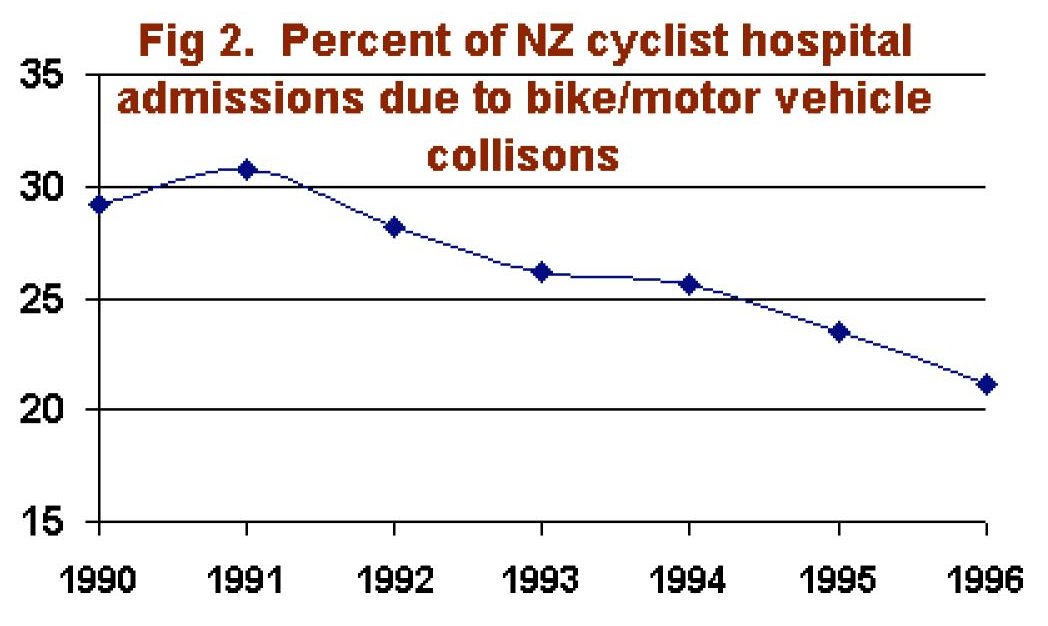

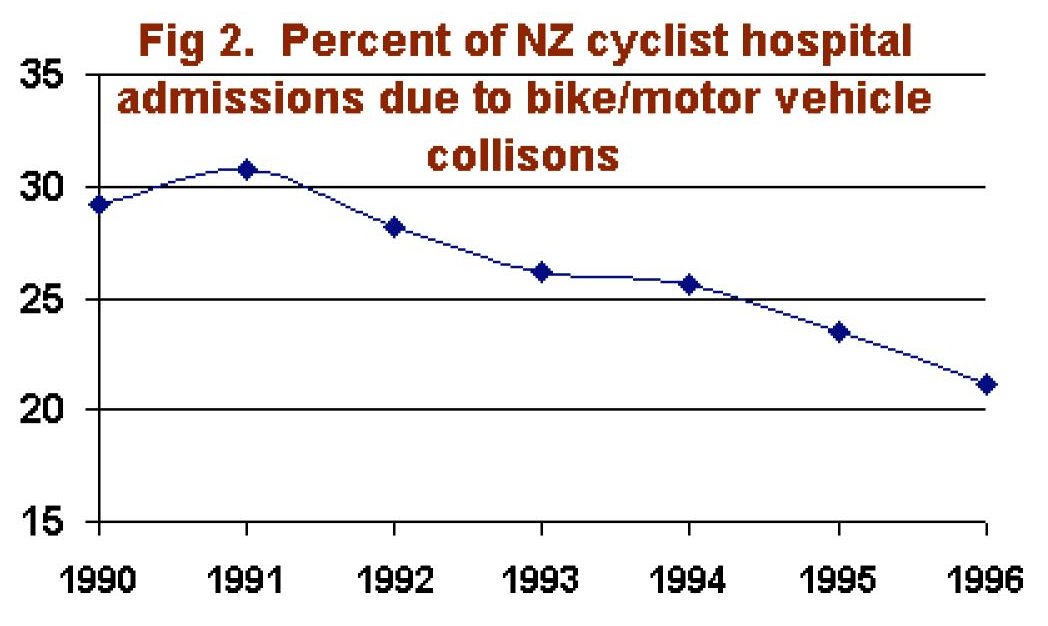

Other trends are evident in injury data to for NZ cyclists. Figure 2 shows a declining trend in the proportion of injuries caused by bike/motor vehicle collisions. This may be due changes in the relative popularity of off-road recreational cycling compared to cycling for transport, or other factors. Gradual trends are common in many time series. Indeed, a gradual change in the popularity of different types of cycling is likely to produce a gradual change in the risk of head injury. There is no reason to attribute this trend to the effect of the helmet law because, like the head injury data in Fig 1, the change is smooth and gradual over a period of several years. There is no sudden jump corresponding to the large increases in helmet wearing with the law.

|

|

Costs and benefits of the helmet law

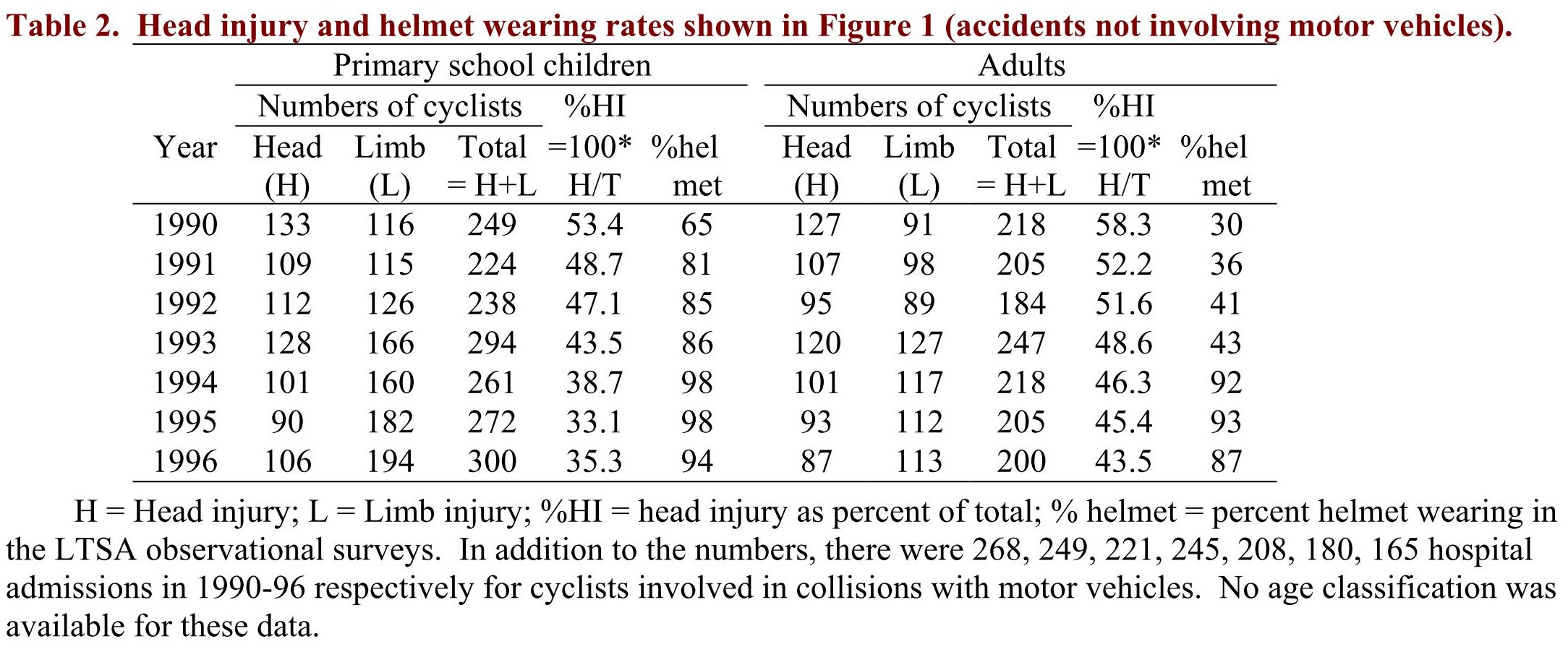

As noted above, if trends were fitted, there was no significant effect of NZ's helmet law. Thus the most likely benefit of helmet law was nothing at all. However, if trends were ignored, Scuffham, Alsop, Cryer and Langley, 2000 estimated a 19% reduction in head injuries. This is a considerable over-estimate, as discussed above. It was nonetheless used by Taylor and Scuffham, 2002 to estimate savings in healthcare costs. Despite use of this unreasonably high estimate of head injury reductions, the estimated savings in healthcare costs are very small (see Table 1).

Adult cyclists were forced to spend nearly NZD 6 million on helmets. As shown in Figure 1, despite this outlay, there was no detectable effect of the increased helmet wearing over and above the trend in head injury rates. However, even if the trend were assumed to be the effect of increased helmet wearing, total averted healthcare costs (NZD 173,158 over 5 years, Table 1) are negligible compared with the cost of helmets. Estimated healthcare costs for head injury are also negligible compared to the health and environmental costs, and expense of alternative transport, for those discouraged from cycling by the helmet law.

For 5-12 year olds, 10,195 helmets were bought because of the law at total cost of NZD 180,792. The estimated annual saving - at most 11.2 hospital bed days - is less than NZD 6,000. Given such unfavourable cost-benefit ratios, the NZ helmet law cannot be justified.

Table 1. Cost-benefit estimates of the NZ helmet law (5-year outcomes and costs in NZD, from Taylor & Scuffham, 2002)

| |

Age 5-12 |

Age 13-18 |

Adults |

| Pre-law wearing rate |

86.8% |

55.9% |

38.9% |

| Post-law wearing rate |

98.6% |

97.1% |

92.9% |

| Number of helmets required |

10,195 |

84,999 |

328,162 |

| Cost of helmets (NZD) |

180,792 |

1,507,312 |

5,819,397 |

| Head injuries averted: |

|

|

|

| Short stay hospital in-patient (no/year) |

3.7 |

9.6 |

25.3 |

| Long stay hospital in-patient (no/year) |

0.3 |

0.7 |

3.0 |

| Total number of bed days averted (no/year) |

11.2 |

33.0 |

95.8 |

| Total health care costs averted (5-year total, NZD) |

28,387 |

75,110 |

173,158 |

Note: Pre-law helmet wearing percentages reported above (from Scuffham 2002) differ slightly from those used by Povey, Frith and Graham, 1999.

Conclusions

Data on head injury rates following the NZ helmet law do not show any real benefit of legislation. Helmets purchased because of the law cost nearly NZD 7.5 million. Estimates of the benefits range from almost nothing to an annual saving in healthcare costs of NZD 55,331. Because the costs of the law are vastly in excess of any possible benefits, very serious consideration should be given to repealing the law.

Appendix 1 - should personal costs and benefits be included in the evaluation of helmet laws?

It could be argued that personal costs to the cyclist, such as pain and suffering, should be included in the estimated benefits of the helmet law. Arguably, other factors such as the inconvenience of helmets, lost health benefits, increased air pollution and costs of alternative transport for those giving up cycling should also be included as costs of the law. However, there is considerable variation in the value individuals place on factors such as pain and suffering, or the inconvenience of helmets. Before legislation, individuals were allowed to weigh up these personal costs and benefits and chose whether or not to wear a helmet. Those choosing not to wear a helmet evidently placed greater personal value on the comfort and convenience of not wear one than on the discomfort of a head injury. The conservative approach to valuing helmet laws, as in Table 1, is therefore to ignore these personal costs because they clearly exceed personal benefits for cyclists choosing not to wear helmets before legislation.

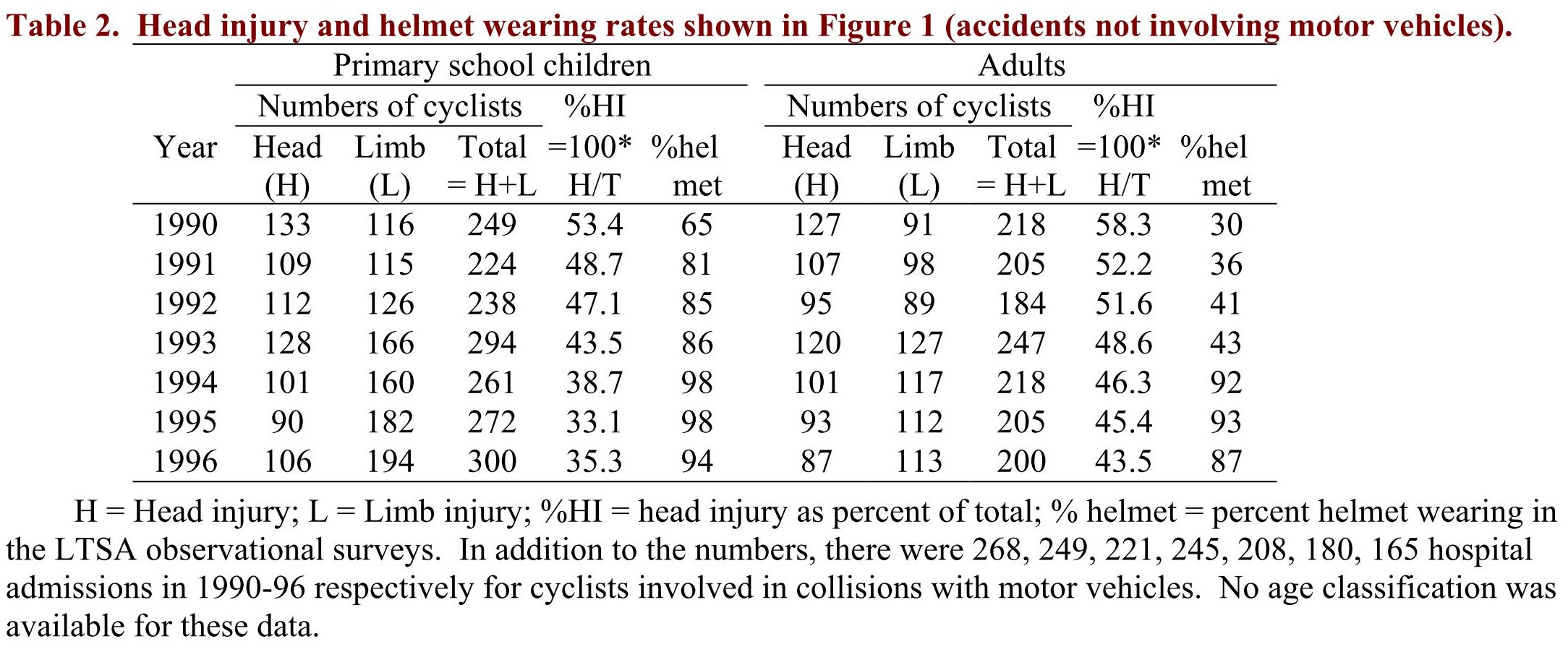

Appendix 2 - Numbers of head and limb injury cases and helmet wearing rates

The data used in Figure 1 and analyzed (Robinson, 2001) were provided by the New Zealand Heath Information Service to the LTSA, who have kindly made them available to others, along with the results of LTSA helmet wearing surveys. Readers are invited to inspect the data for themselves and use common sense to examine the plausibility of any claims that the helmet law had any significant effect on head injuries. Head injury cases were defined as cyclists with skull fractures or intracranial injury (including concussion; ICD codes 800-804.99, 850- 855.99). Limb injury cases were defined as cyclists with a limb fracture (ICD code 810-929.99) but no head injury. Helmet wearing rates, based on observations at 60 survey sites in towns and suburbs throughout NZ, differ slightly from those used by Taylor and Scuffham, 2002 for the economic analysis reported in Table 1.Figure 1 is based on accidents not involving motor vehicles. Bicycle helmets are not designed to prevent the severe head injuries that may arise from bike/motor vehicle collisions so no attempt was made to analysed injury data from bike/motor vehicle crashes.

References

Hendrie, Legge, Rosman and Kirov, 1999

Hendrie D, Legge M, Rosman D, Kirov C, 1999. An Economic Evaluation of the Mandatory Bicycle Helmet Legislation in Western Australia. Road Accident Prevention Research Unit .

Povey, Frith and Graham, 1999

Povey LJ, Frith WJ, Graham PG, 1999. Cycle helmet effectiveness in New Zealand. Accident Analysis & Prevention 1999 Nov;31(6):763-70.

Robinson, 1996

Robinson DL, 1996. Head injuries and bicycle helmet laws. Accident Analysis & Prevention 1996 Jul;28(4):463-75.

Robinson, 2001

Robinson DL, 2001. Changes in head injury with the New Zealand bicycle helmet law. Accident Analysis & Prevention 2001 Sep;33(5):687-91.

Scuffham, Alsop, Cryer and Langley, 2000

Scuffham P, Alsop J, Cryer C, Langley JD, 2000. Head injuries to bicyclists and the New Zealand bicycle helmet law. Accident Analysis and Prevention 2000 Jul;32(4):565-73.

Taylor and Scuffham, 2002

Taylor M, Scuffham P, 2002. New Zealand bicycle helmet law - do the costs outweigh the benefits?. Injury Prevention 2002;8:317-320.